Aziz Ahmed Jamali

In 2017, Zaheer Durrani became friends with me, on Facebook; as it happens with people from Balochistan, our interaction increased leading us towards an adventure equally attractive for many around. One day, Zaheer called me from London, He’s member of the London Mountaineering Club and residing there for many years now, and exchanged articles and photos published in the 1937 edition of The Himalayan Journal Vol. 09; it explained how the young Lieutenant J.R.G. Finch of Great Britain’s Royal Engineers had climbed “The Great Step” in Takatu Hills north of Quetta. Joined by R.K. Hamblin of Royal Air Force, Finch also climbed the “Thorn Bush” route in the same vicinity.

We consulted more with Doda Baloch, our friend who had done climbing during his stay in the US. Zaheer shared his plan for September 2017 while I agreed to do reconnaissance (recce) of the terrain with Doda. We did a successful recce trip and located not only Finch’s route on the Great Step but also the Thorn Bush crack.

Zaheer traveled to Pakistan and did some sport climbing in the Margalla Hills, Islamabad. After he arrived in Quetta, one afternoon we decided to practice basic climbing skills and went on another recce trip to Takatu. His father Sardar Zahoor Durrani also joined to surprise us in proving himself a better trekker at 77 years of age. I did my first ever climbing practice that day; I was introduced to climbing gear and was instructed in using a harness, tying a figure of eight, belaying, and abseiling. We were joined by interested fellows from Quetta.

On 21st September, the D day, we drove early morning to Nagha Village in Sra Khula Valley; it’s a brief jeepable trek from Kachh Road. Lt. Finch’s description of the route mentions the approach to the route as ‘leave the car at eighteen miles’ By 11 am we were at the foot of the climb and were all set for climbing in a trio: Aziz (myself), Doda Baloch and Zaheer as the lead climber. We were joined by a ground team of six additional people to add to the experience and fun. The wishful plan was to climb Finch’s route and make it to the top 9 pitches. Our ground party was advised to proceed to the top of the shelf via a walking trail and their rendezvous with us at the end of our climb.

Our first three pitches took us two hours to negotiate, with the third pitch being more likely of a British climbing grade ‘Severe’; we were easily followed by Bismillah and Hannan who dared scrambling up via an alternate route without gear. They found out a shortcut, a walk-able ledge leading to an exit into a nullah discharge, courtesy of local shepherds. Other fellows cheered us from the ground and waited until we went out of sight at the fourth pitch. Here, seeing that the steep crags were too risky and exposed for an unprotected climb, Bismillah and Hannan bid us farewell and returned to join the ground party.

The fourth pitch warranted negotiating a Nullah, water stream, which hosted wild fig trees and overgrown thorn- bushes, thronging most of our way in the boulder-strewn passage. This Nullah also seemed to be an abode of Markhors, wild mountain goats, as evidenced by fresh scat which we discovered on the ledges on our way up. We tried to match the route and terrain with the details given in the published article. Although major features could be easily compared with those in the literature, many things had changed; both overgrown bushes and a magnificent confusion of minor spurs on the ragged cliffs detained us to some extent from locating Finch’s original route.

We climbed 5th and 6th pitches, both around 60 feet long and of British ‘Very Difficult’ grade, fully following Zaheer and aptly utilizing the 180 feet rope.

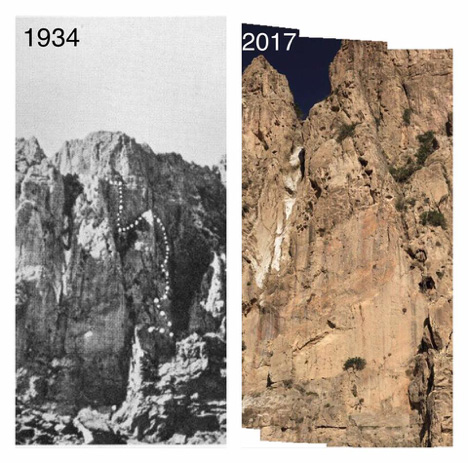

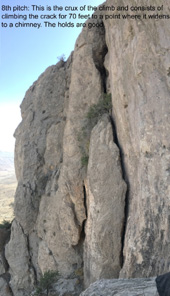

In the published article, the 7th pitch was described as ‘descent on the Southside and walk over to the foot of an obvious crack’. However, a closer look at the crack (Start of 8th pitch & the crux) revealed that the crack had widened to about 1-2 feet and offered no natural features to protect the climb. Both sides of the crack were featureless smooth limestone.

We had reached 8500 feet above sea level. Our target, the culmination of The Great Step climb, was at around 8750 feet above sea level; We looked for alternative routes, tried here and there, up and down but the route had been altered ostensibly due to earthquakes and decades of weathering since the 1934 climb. A few promising cracks had opened up but any possible climbing was to be undertaken on exposed rocks and likely without protection. We studied the cliff for half an hour from our final landing, scoping out possible routes up, but it being late in the afternoon, we reached a consensus and called it a day. It was a hard decision however and we decided that the sensible course of action was to make a Thumbs Down Selfie and braced for our descent at 4.30 pm.

We decided to sacrifice slings and carabiners to set up anchors for abseiling down pitches 6 & 5. I was new to climbing and feared a lot while abseiling on return. Dusty bush and tree en route posed a lot of difficulty to us, throwing us into fits of vociferous coughing as we pushed our way through them. Zaheer is not only an excellent climber but encouraging leader. He held and helped us with lifelines on narrow landings/ledges. His years of climbing experience spoke in his nonchalant yet careful way of approaching the cliff, something which had a vicarious and confident effect on me and Doda.

Find of the day: At the top of the 5th pitch, Zaheer discovered a metal spike with a full ringlet, lying in a 2-inch wide crack, ostensibly used as a piton by the team who climbed in 1934. It could have acted as an anchor, hammered in a narrow crack; however, the crack had opened up after over eighty years of seismic activity and weathering, leaving the piton loosely in place in the crack. This find established two facts about the climb. Firstly, that the route has not been climbed in many decades and secondly, that we were indeed on the very route that Lt. Finch climbed in 1934 and referred to as a ‘Classic’ by Marples & Thomson in 1940, The Himalayan Journal Vol. 12.

During the descent, we observed possibilities for future climbing, albeit of much harder grades, in different directions, especially above the Nullah. We walked down our last four pitches swiftly and without placing protection, scrambling down sections which were steep but never difficult; a narrow cleft was very interesting as we had to drop into it one by one to wriggle out onto a ledge, leading us to the foot of the cliff. This final walk-able ledge was also the route that Bismillah and Hannan had availed as they followed our climb up to our 4th pitch. The three of us reached down by sunset; our ground team was still awaiting us on the shelf atop the cliff and was called to walk to the vehicles. We walked out in climbing shoes, a hard job, and made it to the vehicles by 8 pm where we were joined by the rest of our team after an hour. We enjoyed a traditional dinner at a local restaurant in Nawakili to end the day in a jolly mood despite all tiredness and a bit of remorse for not being able to climb up all along the Great Step, in the footsteps of Lt. Finch.

The effort was an achievement in itself, being a rare climbing expedition in Balochistan; we covered seven out of nine pitches but retreated before proceeding to the last two steps as we felt that the 8th pitch was not climbable safely anymore. Yet we hope to let the efforts grow.

I feel extremely grateful to Zaheer Durrani for making it possible and to Doda for facilitating all along. Zaheer gifted some of his climbing equipment to local climbers of Quetta so that other enthusiasts may adopt and continue the sport in the future.

Doda Baloch and Zaheer Durrani also contributed to this report.

Click here to read other stories written by Aziz Jamali

Share your comments!